pra lá de duas horas brutais com eduardo bueno no porão de dylan & the band

vem de novo…

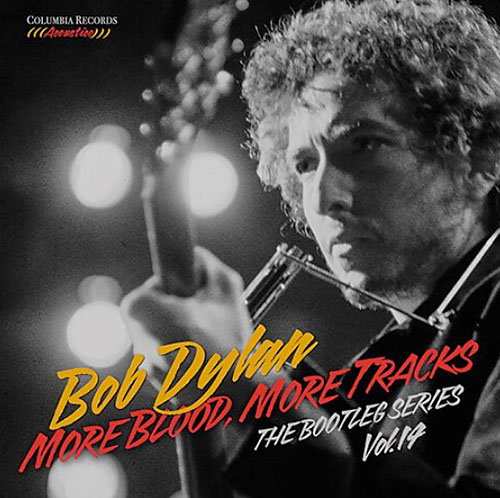

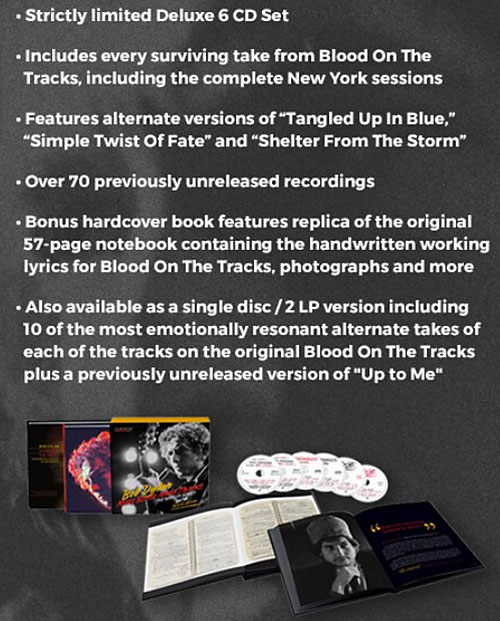

roNca roNca cravado a fogo em nossos corações, em 30dezembro… colocando a tampa, inoxidavelmente, em 2014, com a caixa “the basement tapes complete / the bootleg series vol11”… contendo seis cds!

mas nada disso teria relevância se não fosse a MEGA descabelada presença a bordo do maior entendido em bob dylan no cone sul: eduardo bueno, o peninha!

CASCA… hoje, aqui mesmo, às 22h

You speak to me in sign language

As I’m eating a sandwich in a small cafe

At a quarter to three

But I can’t respond to your sign language

You’re taking advantage, bringing me down

Can’t you make any sound?

It was there by the bakery, surrounded by fakery

This is my story, still I’m still there

Does she know I still care?

Link Wray was playing on a jukebox, I was paying

For the words I was saying, so misunderstood

He didn’t do me no good

You speak to me in sign language

As I’m eating a sandwich in a small cafe

At a quarter to three

But I can’t respond to your sign language

You’re taking advantage, bringing me down

Can’t you make any sound?

(Bob Dylan)

Bill Flanagan: A few years ago I went to one of your concerts and found myself sitting next to Ornette Coleman. After the show I went backstage and there were some very famous rock musicians and actors waiting around, but the only person you invited into your dressing room was Ornette. Do you feel a connection with those jazz guys?

Bob Dylan: Yeah, I always have. I knew Ornette a little bit and we did have a few things in common. He faced a lot of adversity, the critics were against him, other jazz players that were jealous. He was doing something so new, so groundbreaking, they didn’t understand it. It wasn’t unlike the abuse that was thrown at me for doing some of the same kind of things, although with different forms of music.